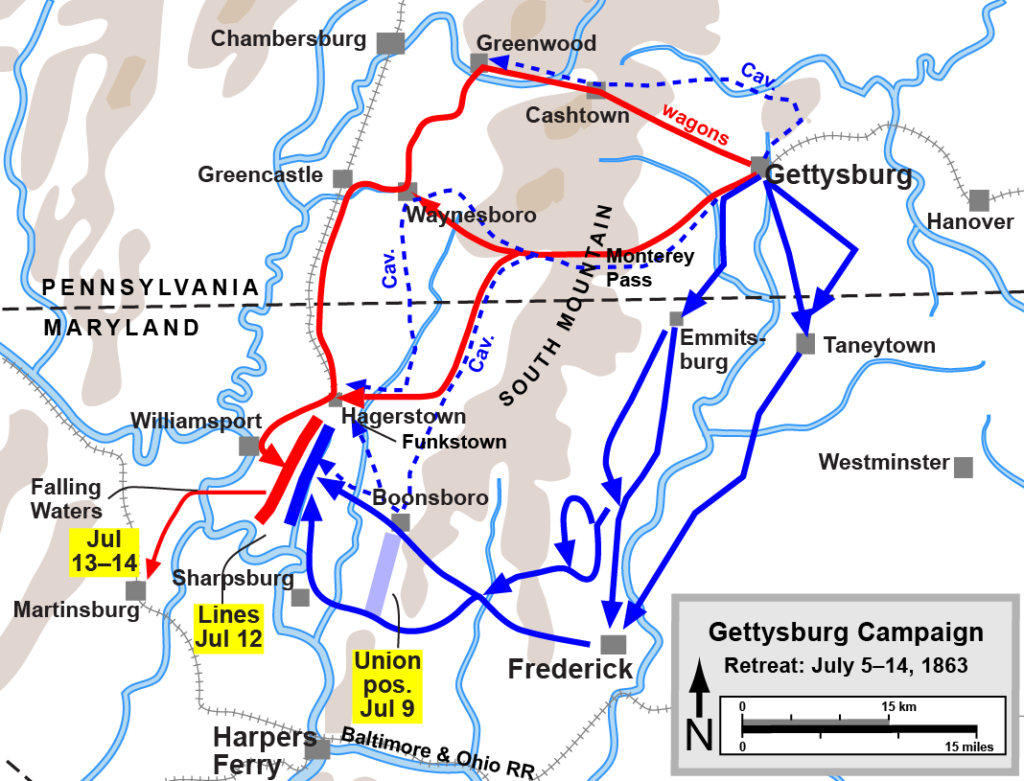

In the aftermath of his loss at Gettysburg, Lee waited for a counterattack which never came on July 4th. That night, in a raging thunderstorm, he began to withdraw his remaining army, all its troops, wounded, weapons and munitions, supplies, cattle and other logistical elements. The retreat took two paths. One, the largest, headed northwest toward Chambersburg, eventually turning south to Waynesboro and Greencastle enroute to Hagerstown. A woman along that route is reported to have watched wagons passing her home for three days.

The other, a 20 mile wagon train, also headed for Hagerstown via Fairfield Pass, Maria Furnace Road and Monterey Pass. Both retreating wagon trains were harassed by Union cavalry. This included Brig Gen George A. Custer against the southern wagon train. A Battle was fought that night near the current location of the Museum.

A Midnight Battle Along the Mason Dixon Line

By John A. Miller, Washington Township Historian

During the morning hours of July 4, 1863, Confederate Major General Robert E. Lee ordered the withdraw of his Confederate Army from Gettysburg. General Grumble Jones volunteered for the task of escorting General Richard Ewell’s wagon train as it traveled through the South Mountain pass of Monterey to Williamsport. Under his command, General Jones had the 1st Maryland Cavalry, Companies B, C, D, and E, and the 6th Virginia Cavalry, a portion of the 11th Virginia Cavalry, and two North Carolina cavalry regiments under the command of General Beverly Robertson. Assisting Captain Emack were portions of Pogue’s and Carter’s batteries, who were serving as couriers and scouts. Through the driving rain, General Ewell’s wagon train rumbled out of Fairfield traveling toward Jack’s Mountain, taking a portion of Iron Springs Road, then through Fairfield Pass by way of Maria Furnace Road to Monterey Pass to Ringgold and then onto Leitersburg.

During the afternoon, as the Confederate Army began retreating through South Mountain, seven miles to the east of Monterey Pass at Emmitsburg, Maryland, General Judson Kilpatrick’s cavalry division came into town. Kilpatrick’s cavalry division consisted of General George Custer’s and Colonel Nathaniel Richmond’s brigades and they were ordered to attack the wagon train that was moving through South Mountain. At Emmitsburg, Kilpatrick was reinforced by Colonel Pennock Huey’s brigade and a battery. Kilpatrick left Emmitsburg and headed toward the mountain.

After arriving at Monterey and seeing the eastern portion of the summit near Monterey Pass was unguarded, Confederate Captain William Tanner ordered one Napoleon cannon to be deployed while the rest of his battery continued westward toward Waynesboro. Captain Tanner ordered the cannon to be deployed in front of what would become the Clermont House, facing the village of Fountaindale. The men of Tanner’s Battery unlimbered the cannon and waited for further orders. The lone cannon had only five rounds of ammunition in the limber chest.

Toward evening, near the hamlet of Fountaindale, Charles H. Buhrman, a local farmer learned of the Confederate retreat at Monterey Pass as well as the capture of several local citizens. He mounted his horse and traveled toward Emmitsburg looking for any Federal soldiers in area. He came across one of General Custer’s scouts and reported the situation on top of the mountain near Monterey Pass.

It was dusk when General Custer’s brigade was at the base of the mountain. The 5th Michigan was the first of Kilpatrick’s cavalry division to climb the mountain. As darkness, and worsening weather conditions began to set in Custer’s men were blinded by the surprised muzzle blast from Tanner’s cannon. The first shot was fired directly into the head of the 5th Michigan Cavalry, causing confusion and chaos in the ranks of the cavalrymen. Two more shots were again fired by Tanner’s men. After the confusion subsided, Emack’s small squad charged and drove the Federals back, where Kilpatrick’s artillery was positioned.

Fearing another Union advance, Captain Emack redeployed his entire force near the Monterey Inn. Orders came to have the cannon redeploy 100 yards from its current position to near the Monterey Inn where Emack’s troopers were positioned on both sides of the road. Meanwhile, Captain Emack rode back toward the road that the wagons were on, trying desperately to get them moving as fast as they could, while struggling to get the other half of the wagon train that was approaching the pass to stop.

General Custer’s brigade reorganized and advanced toward the summit. For the next several hours in the rain and darkness, the opposing forces engaged in some of the most confusing and chaotic fighting of the Civil War. In some instances, the soldiers could only tell where the enemy was by flashes of the muzzle from their guns, the cannon or lightning in the sky that illuminated their positions.

Gaining the eastern side of the summit, Kilpatrick ordered the 1st Vermont Cavalry to Leitersburg in order to attack the Confederate wagons as they came off of South Mountain. He also ordered a portion of the 1st Michigan Cavalry to attack Fairfield Pass, one mile east of Monterey Pass.

Near the Monterey House, General Kilpatrick deployed a section of artillery and shelled the Confederate battle lines that were positioned near the modern day Lion’s Club Park. By 3:00 am, along a creek just west of the Monterey House, Custer’s men, supported by artillery, dismounted and attacked Captain Emack who was near the Tollgate house. Fighting raged in the woods near the modern day intersection of Route 16 and Charmain Road, leaving Captain Emack wounded by shell, shot, and a saber. As the battle of Fairfield Gap came to a close, Captain Emack was finally reinforced by other companies of the 1st Maryland Cavalry as well as the 4th North Carolina Cavalry, as Custer’s men approached. During the thickest of the fight, General Jones ordered his couriers and staff officers to get into the fight as well as the wounded that could fire a gun.

The 5th and the 6th Michigan Cavalry were ordered to dismount, leaving the 7th Michigan and two companies of the 5th Michigan in reserve. While Custer was rallying his men, a bullet struck his horse. It was at this time that the 1st West Virginia Cavalry and a portion of the 1st Ohio were ordered to the front to support Custer’s bogged down battle line. The West Virginians charged the Confederate cannon, tumbling it down the embankment and began destroying wagons and taking on prisoners.

The Sharpshooters of the 1st North Carolina Battalion and the 6th Virginia Cavalry arrived in time to halt the wagons approaching from Fairfield Gap. Two guns from Pennington’s Battery poured case shot into their ranks from their position near the Monterey Toll House. During the fight, the 6th Virginia Cavalry retreated back toward Fairfield, refusing to come up until after daybreak. The sharpshooters might have saved the rear of the wagon train, but the wagons that were traveling toward Waterloo were in grave danger.

As soon as the West Virginians cleared the pass and began its charge down the mountainside, Custer and his troopers finally began storming through the long line of wagons, “like a pack of wild Indians” overturning many wagons and setting fire to others as the Union cavalry collected their bounty until dawn. In some instances, panic stricken horses with no where to go fell off the mountain cliffs and overturned into the steep ravines. At the bottom of the mountain sat several hundred wagons guarded by the 36th Virginia Cavalry. In the wake of the Union charge, the 36th Virginia had no chance and withdrew from the battlefield.

While the wagons at Waterloo were under attack, back at Monterey Pass, just before daybreak, Chew’s Battery, the 6th Virginia Cavalry as well as General Iverson’s North Carolina Brigade arrived. General Wright’s Brigade was a few hours behind, forcing Kilpatrick to give up the fight at the actual mountain pass. Realizing that his cavalry was divided at Leitersburg and Waterloo, Kilpatrick withdraws from Monterey Pass fighting remains of Confederate cavalry units down the mountain.

The fight then continued into Maryland, making this battle the only one fought on both sides of the Mason and Dixon Line. Once Kilpatrick was at Ringgold, Maryland he ordered his cavalry to halt. The wagons that were not destroyed were burned in the open fields at Ringgold. A portion of the 1st Vermont Cavalry met Kilpatrick at Ringgold after the destruction they caused at Leitersburg.